Flocean, a Norwegian company, is set to open the world’s first commercial-scale subsea desalination plant, an approach that could cut the cost and energy used to make seawater drinkable

Turning seawater into drinking water is so costly and energy-intensive that it’s untenable in most parts of the world, but a Norwegian company is trialling a new approach that could change that. Flocean will launch the world’s first commercial-scale subsea desalination plant in 2026, and says its system will cut the cost and energy consumption of the process dramatically.

Global demand for water is going up, driven by population growth, climate change and industrial uses like data centres and manufacturing. Meanwhile, fresh water is becoming less abundant due to droughts, deforestation and over-irrigation.

Land-based desalination currently produces about 1 per cent of the world’s fresh water supply, with over 300 million people relying on this source for their daily water needs. The biggest plants are in the Middle East, where cheap energy makes the technology more feasible and water scarcity makes it more necessary.

The leading technology for desalination today is reverse osmosis. The method pumps seawater through a membrane with microscopic holes that only allow water molecules to pass through, while salt and other impurities get filtered out. The water has to be pressurised to push it through the filters, a process that requires vast amounts of energy.

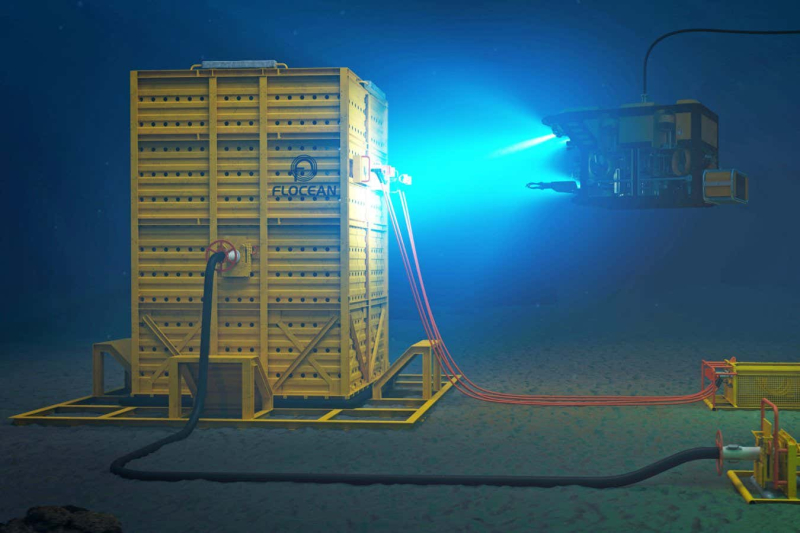

Flocean’s approach is to plunge water-filtering pods deep into the ocean, separate seawater from salt at depth, then pump the fresh water back up to land. By putting reverse osmosis pods deep underwater, the technology leverages hydrostatic pressure – the weight of all the water pressing down from above – to push the seawater through filtering membranes.

Less pumping means less energy consumption, around a 40 to 50 per cent reduction compared with conventional desalination plants, according to the company. Plus, seawater is cleaner once you get below the sunlight zone (which extends to 200 metres below the water’s surface), which means the water doesn’t require as much pre-treatment before it reaches membranes.

“It’s fundamentally quite boring down there from a process and engineering perspective,” says Alexander Fuglesang, Flocean’s founder and CEO. “It’s the same salinity, temperature, pressure. It’s dark. There’s not a lot of bacteria that can cause biofouling.” The same hydrostatic pressure that pushes water through the membranes also helps disperse the salty brine by-product, which Flocean says is free of chemicals that might harm marine life.

For the past year, Flocean has been desalinating water at a depth of 524 metres at its test site at Norway’s largest offshore supply base, Mongstad Industrial Park. Its commercial facility, called Flocean One, is being built at the same location, and will initially produce 1000 cubic metres of fresh water daily when it launches next year. The operation can then be scaled up modularly by adding more desalination pods.

“Our philosophy is to keep the subsea units the same and scale by multiplication rather than by building ever bigger machines,” says Fuglesang. Scaling up will involve engineering trade-offs at the system level, however. Since more modules will share the same power supply and controls, Flocean’s engineers need to organise power distribution and the permeate manifold – the mechanism that directs purified water from multiple membranes to a single output line – so that scaling up is as straightforward as possible.

“This solution could become viable in suitable locations, providing affordable water if costs decline, but it has yet to be proven at large scale,” says Nidal Hilal at New York University Abu Dhabi. “Broad municipal deployment likely depends on overcoming technical and economic challenges over several years.”

Cost reductions will be crucial to scale up the technology further, says Hilal, as it is still much more expensive than obtaining fresh water through conventional methods like pulling from lakes or aquifers.

Cleaning and maintaining the membranes will be one of Flocean’s biggest costs. Advances in membrane technology will help; Hilal’s research group is working on electrically conductive membranes that use electricity to repel salt ions and foulants, keeping themselves clean and boosting throughput. The researchers are also exploring ways to recycle single-use plastics into membrane materials, increasing sustainability while further reducing costs. “More durable membranes and high-efficiency pumps can further lower operational expenses, while renewable energy integration reduces power costs,” says Hilal.

Flocean One should start producing fresh water in the second quarter of 2026. If the technology works as planned, it could help Flocean get the backing to build bigger plants elsewhere. “The biggest challenge for us is having perfect alignment,” says Fuglesang. “We need the client, we need government permissions and we need strong financial partners.”